In 1856, then governor Sir John Bowring proposed that the constitution of the Legislative Council be changed to increase membership to 13 members, of whom five would be elected by landowners enjoying rents exceeding 10 pounds. This attempt at an extremely limited form of democracy (there were only 141 such electors, of whom half were non-British) was rejected by the Colonial Office on the basis that Chinese residents had no respect “for the main principles upon which social order rests.”

Popular grassroots movements were regarded as being greatly discomforting by the authorities. When Asian workers rioted in 1884 after some of their number were fined for refusing to work for French traders, the Peace Preservation Ordinance was enacted, outlawing membership of any organization deemed “incompatible with the peace and good order of the colony”. Censorship was imposed on the press.

Hong Kong’s non-elites repeatedly demonstrated their political engagement. They showed their unwillingness to come under government controls and took strike action frequently to protect their freedoms. General and coolie strikes erupted in 1844, 1858, 1862, 1863, 1872, 1888 and 1894.

In response to the Chinese revolution, the Societies Ordinance was passed, which required registration of all organizations and resurrected the key test seen in the 1884 legislation for ruling them unlawful. The ordinance went further than its predecessor by explicitly targeting chambers of commerce. The administration was particularly concerned about suppressing any activity which might contribute to Hong Kong playing an active role in the tumult across the border. The ordinance banned the free association of workers in unions, imposing restrictive bureaucracy on registration and stringent monitoring of meetings proposed.

In the 1920s, workers were organized through labor-contractors who, in parallel with the trading system which enriched the all-powerful compradors, provided a communication channel between the management of foreign hongs and their workers, but entirely for the benefit of the labor contractors. Workers were powerless and roundly exploited under the system.

In 1936, the Sanitary Board was reconstituted as the Urban Council and included eight appointed non-Official members, including three of Chinese extraction.

Ultimately, however, Governor Grantham allowed minor reform proposals and, as a result, two pre-war existing seats in the virtually powerless Urban Council were directly elected in 1952; this was doubled to four the following year. In 1956, the body became semi-elected but on a restricted franchise, which had expanded from some 9,000 registered voters in 1952 to only about 250,000 eligible voters 14 years later. Eligibility reached about half a million in 1981 but only 34,381 bothered to register, probably on account of the fact that the body’s powers extended only to cleaning, running bathhouses and public lavatories, hawker control, supervising beaches, burying the dead, and the like.

Records declassified in 2014 show discussions about self-government between British and Hong Kong governments resumed in 1958, prompted by the British expulsion from India and growing anti-colonial sentiment in the remaining Crown Colonies. Zhou Enlai, representing the CCP at the time, warned, however, that this “conspiracy” of self-governance would be a “very unfriendly act” and that the CCP wished the present colonial status of Hong Kong to continue. China was facing increasing isolation in a Cold War world and the party needed Hong Kong for contacts and trade with the outside world.

Liao Chengzhi, a senior Chinese official in charge of Hong Kong affairs, said in 1960 that China “shall not hesitate to take positive action to have Hong Kong, Kowloon and New Territories liberated” [by the People’s Liberation Army] should the status quo (i.e. colonial administration) be changed. The warning killed any democratic development for the next three decades.

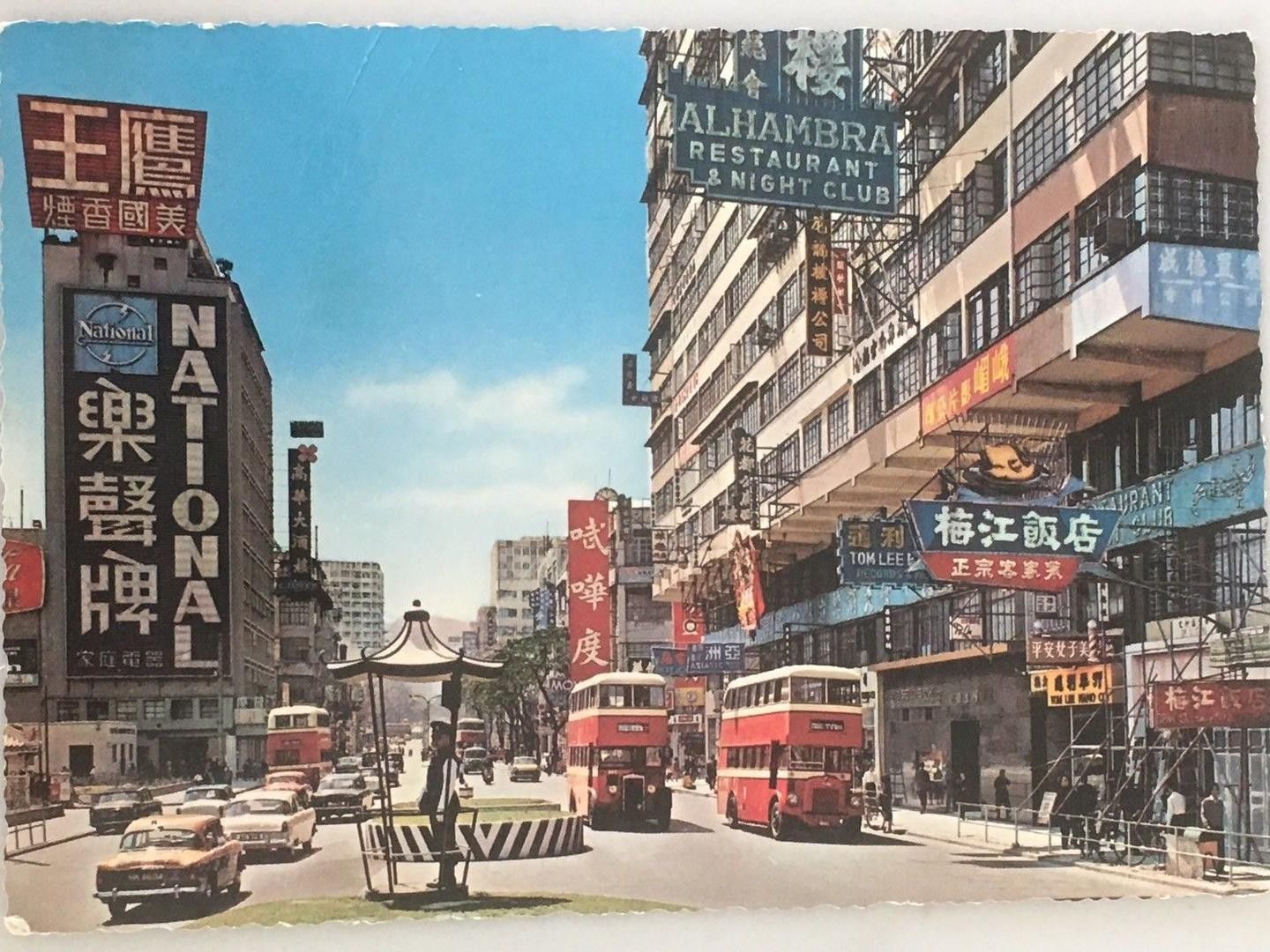

Two significant protest movements also occurred during this period. One in 1966, due to the fare increase for travel on the cross-harbor Star Ferry. Another erupted in 1967, under the influence of the cultural revolution in the mainland. The 1967 social movement began with protests against the colonial rule but later developed into riots, including planting bombs and committing arson. Most Hongkongers stood by the colonial government during the protest.

In the absence of democratic legitimacy, the colonial government slowly implemented a system of formal advisory bodies, integrating interest groups into the policy-making process during the 1970s, which enabled grievances and controversies to be discussed and resolved.

Meanwhile, in year 1972, the People’s Republic of China after obtaining the seat of China in the United Nations in the year before, claim Hong Kong (and Macau) are within Chinese sovereignty, thus they are not colonies in the ordinary sense, therefore should not be listed under the United Nations list of non-self-governing territories, and caused the removal of both cities from the list. Entities in the list were entitled to self-determination and independence, according to United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1514.